To an outside observer, the fruits of our brainstorm sessions can seem like magic. People often wonder where our ideas come from & chalk it up to us having some secret process or capability. The truth is I work with a lot of talented, creative people so to some extent, it is magic. The caveat is that without clarity as to what problem or unmet need is, the chance of coming up with a relevant solution is pretty slim. Particularly when you need to innovate on demand.

To an outside observer, the fruits of our brainstorm sessions can seem like magic. People often wonder where our ideas come from & chalk it up to us having some secret process or capability. The truth is I work with a lot of talented, creative people so to some extent, it is magic. The caveat is that without clarity as to what problem or unmet need is, the chance of coming up with a relevant solution is pretty slim. Particularly when you need to innovate on demand.

This challenge of defining the problem before attempting to solve it also comes up when individual inventors approach us. Often they’ve come up with a solution, and are ardently trying to find a problem or application they can apply their idea to. Sometimes, drawing from their personal experience, they hit the nail right on the head. Sometimes, not so much.

When most people think of product research, visions of focus groups, one-way mirrors and ad men spring to mind. This kind of research is predicated on a user being aware of what’s confounding them, and being able to articulate it.

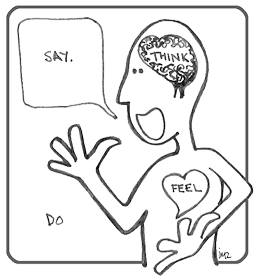

Enter ethnography (also known as contextual research), which is a methodology developed to try and get beyond a user’s verbally stated preferences and understand what actually motivates their behavior. As I attempted to convey in the cartoon, the interactions, overlaps, and inconsistencies between what a user thinks, feels, does, and says are fertile sources of insight into how to make their experience more satisfying. Think of ethnographers as the Jane Goodalls of the product world; by watching users in their natural habitat and by observing rather than leading the interaction, we can often identify obstacles or barriers in a user’s path, conscious or subconscious workarounds, and areas of opportunity for a breakthrough product.

In contrast to a focus group, we’re not trying to determine simple preferences such as color or button shape, but looking to understand the fundamental needs or desires a successful product will address. To do that, we go deep into a small number of user’s experiences rather than cover a large sample population in a shallow way.

Over the past two decades I’ve had the opportunity to contribute to dozens of user research efforts examining product experiences as diverse as space & military hardware, furniture, children’s toothbrushes, soft goods, personal electronics, surgical tools, medical devices, information systems and all sorts of user interfaces. I’m looking forward to sharing some of those stories here.